By Janis Kreilis

In March 2017, the Trump administration began unpicking an array of environmental rules passed during Obama’s time in the office, including the Clean Power Plan. The White House also directed federal agencies to put the finalization of new regulations on hold until the administration could examine them.

In this change of direction, several regulations aimed at improving the efficiency standards of appliances that were already finalized but not published in the Federal Register due to a 45-day waiting period.

Environmental groups and some state and city governments led by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman have warned the Trump administration of their intent to sue the White House if the rules are not published. The potential plaintiffs argue that the administration is violating the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) of 1975 and the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946.

The relatively common-sense efficiency rules for products like ceiling fans, portable air conditioners, walk-in coolers and freezers, and commercial boilers were part of a non-partisan effort. Together, the rules would save consumers more than $11 billion over 30 years, despite some complaints by manufacturers of increased costs.

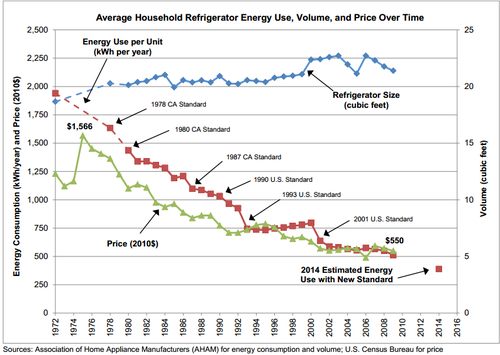

It is rare for energy efficiency standards to come to the fore of the national debate on energy policy and regulation. Through the years, the federal government has periodically updated them without much controversy. California was the first state to set efficiency standards in 1974. In 1975, the federal government followed suit with the EPCA. The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1987 widened the scope and established minimum standards for common household appliances. The Energy Policy Act of 1992 and two more acts in 2005 and 2007 updated the existing standards and expanded the list of appliances covered.

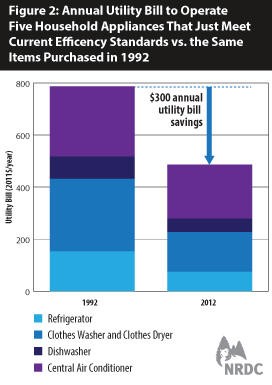

Today, most of the everyday appliances in the U.S. are covered by efficiency standards, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). One of the main reasons they have avoided controversy is the simple fact that they work: the Department of Energy estimates they save consumers about $62 billion yearly (or about $300 per household).

Examples abound: fridges in 1973 used four times the energy than fridges today while being twice more expensive and about 15% smaller. New washing machines use 70 percent less energy than the ones in 1990. The figures for air conditioners and dishwashers are 50 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

Examples abound: fridges in 1973 used four times the energy than fridges today while being twice more expensive and about 15% smaller. New washing machines use 70 percent less energy than the ones in 1990. The figures for air conditioners and dishwashers are 50 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

Nor have they made appliances more expensive. By letting the manufacturers figure out how to meet the standards, the regulations have incentivized innovation. Even in cases where the Department of Energy anticipated price increases, retail prices have dropped instead. The trends in fridge prices, capacity, and energy use offer a great point (and this list does not include carbon savings).

It would be unwise to let energy efficiency standards get caught in the crossfire of today’s political climate. As boring as they may seem, the standards have proven successful by quietly working behind the scenes.

If the federal government is reluctant to continue down this path, some states might, as in the case of California, which became the first to adopt efficiency standards for computers in December 2016. However, for manufacturers distributing goods nationwide, keeping track of the different state-level regulations could be even more painful. It’s a probably good idea to take the federal ones out of the freezer.

Source: NRDC.