It has a hidden value that not everyone can see

By Janis Kreilis

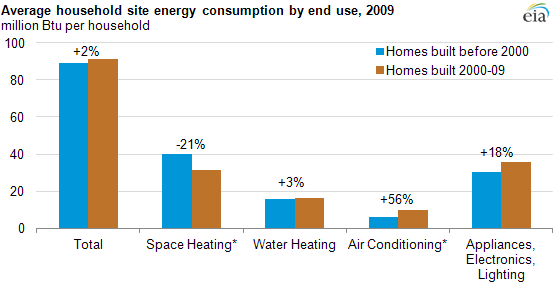

Residential energy efficiency has shown significant improvements over the past few years. In 2013, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that heating and cooling – the long-standing energy hogs in American homes – no longer accounted for the major part of energy use in homes. Whereas in 1993, heating and cooling comprised 57.7% of total energy use, by 2009, their share had declined to 47.7%. Meanwhile, the share of appliances, electronics, and lighting has risen by almost 40% thanks to our flat-screen TVs, gaming consoles, margarita machines, and slow cookers.

Source: EIA

This finding becomes even more fascinating when considering the fact that, while total energy use has only risen by about 2%, our homes today are 30% larger than they were before 2000.

Source: EIA

The EIA attributes this to improvements in heating technology and building shells: our new houses have better boilers and insulation. However, a lot remains to be done. According to the Department of Energy, the average American could be wasting $200 to $400 of their annual energy costs (roughly $2000) on drafts, air leaks, and outdated heating and cooling systems. That’s 10-20% going (literally) out the window.

Although efficiency improvements might seem common-sense, several factors help explain why more people do not fix their homes. First, those changes are often capital-intensive. Boilers, insulation, windows, and the labor required to install them cost more than many people can easily afford.

Second, the savings themselves are intangible, which can affect people’s perception of them. Third, estimating savings and then reaping the rewards from efficiency improvements require a careful analysis of the consumption data from the building over a longer period of time since weather affects energy use in homes in a major way. Trust between the customer and the contractor is essential as well: to cut down the energy use of a building, the repairs and upgrades have to be executed properly.

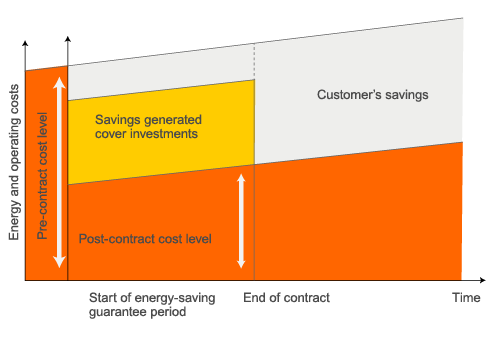

The industry has tried to come up with several innovations in financing models to overcome some of these difficulties. One of the older models, in which an energy service company (ESCO) finances the retrofits but then captures part of the savings until a certain pre-agreed payback is reached, has met considerable success in the commercial sector and made inroads in the residential sector as well.

Source: Swedbank

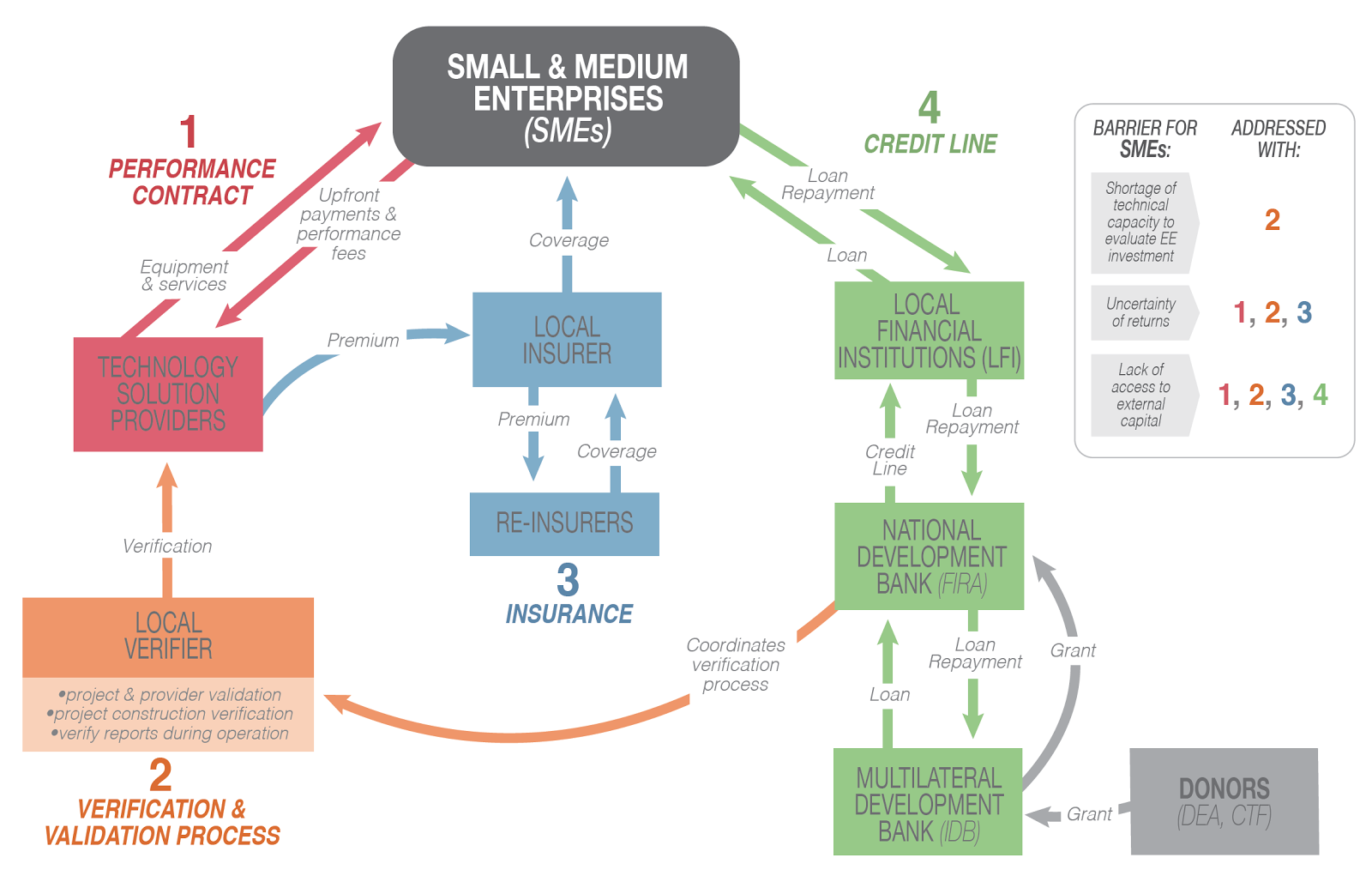

A more novel idea is energy savings insurance. Essentially, this adds certainty for the customer that the savings estimated by a technically competent contractor will also be realized after the retrofits. This approach can be highly beneficial for small and medium enterprises and has been deployed in a number of developing countries.

Source: Climate Lab

In New York, an energy software company called Sealed recently implemented an energy savings insurance program for the residential market in partnership with the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (HSB), part of Munich Re. Sealed has developed data-based analytics that can predict the energy savings from a particular house after the retrofits, and the insurance removes the performance risk increasing the confidence of third-party capital providers. Sealed provides zero upfront cost efficiency retrofits in collaboration with New York Green Bank, a $1-billion investment fund set up in late December 2013. The credit line allows the company to avoid asking their customers to take out loans for financing their efficiency upgrades, which the average homeowner has been averse to.

Although securitizing efficiency improvements has not been as successful as that of solar loans or power purchase agreements, NY Green Bank could be among the first institutions to crack the simple-yet-complicated energy efficiency conundrum. Watch this space.