By Janis Kreilis

For anyone following the debates on net metering nationwide, Nevada has provided a steady stream of events to talk about since 2015, when the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada (NV PUC) eliminated retail-rate net metering and replaced it with much lower wholesale rates.

Now, net metering for all customers is back on the table. Earlier this week, Nevada Assemblyman Justin Watkins (D) introduced AB 270, a bill that requires regulators to revisit the value of solar debate and sets a base export rate of at least $0.09/kWh, in addition to $0.02/kWh for the environmental benefits of solar.

Watkins has acknowledged that passing the bill into law would be difficult. However, the prolonged battle over net metering alone just shows how important getting this policy right will be not just in Nevada, which is among the leading solar states in the U.S., but in other states nationwide.

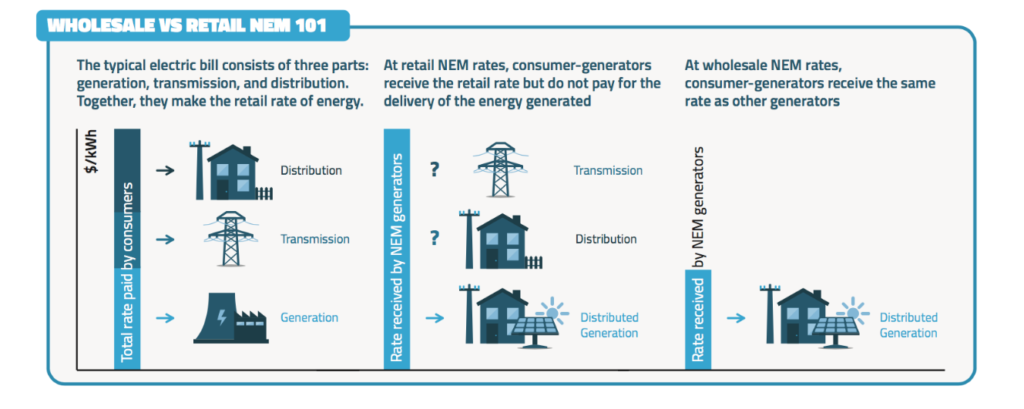

On its face, net metering is a simple and powerful policy tool to encourage distributed generation such as solar panels. When the customers generate more energy than they consume, the energy flows back into the grid. This “export” flow is tracked by a smart meter, and, under retail-rate net metering, the consumer-generator receives the same amount per kWh that they would have paid otherwise.

Net Metering Explained. Source: EnerKnol.

The problem, however, is that the retail rate contains not only the cost of generation but also transmission and distribution – in other words, getting the energy to the door. When consumer-generators export their kilowatt-hours, they receive a much higher compensation than large generators participating in the wholesale market.

This difference must be covered by other grid users who essentially subsidize distributed generation by paying for grid maintenance. While the share of rooftop solar, for example, in the overall generation mix is small, this subsidy does not matter much. However, at higher levels of generation, this issue of fairness cannot be easily ignored anymore.

In December 2015, the NV PUC decided to change the policy course abruptly by ending retail-rate net metering and replacing retail rates to wholesale rates in addition to increasing fixed charges. Importantly, the PUC also applied these rates to existing customers retroactively.

A public backlash ensued. Two major solar companies, SolarCity and Sunrun, announced that they ceased all operations in the state, and the new policy was challenged in court.

Since then, the NV PUC has backpedaled on its decision. In September 2016, existing customers were grandfathered. In the beginning of January 2017, the commission restored net metering for the customers of NV Energy’s Sierra Pacific Power Company.

Other states facing similar issues have learned some lessons from Nevada. In Arizona, the Corporation Commission (AZ CC) first conducted a value of solar study, working with the stakeholders to devise a fairer way to compensate distributed solar. In March 2017, the AZ CC set new rates for the customers of one of the largest utilities that still grandfathered existing customers for twenty years.

New York, too, has been proactive in working with its utilities on this issue. Under its Value of Distributed Energy Resources proceeding, the New York Public Service Commission recently announced plans to implement a new way of compensating distributed generation through a “Value Stack” concept based on locational and environmental benefits.

One of the takeaways, then, would be to work with the local stakeholders in developing transition plans and ensuring the continuity of policy for existing customers.

However, even in the most favorable states for solar, the net metering subsidy plays an important role. Hawaii, which is by far the number-one state in terms of solar generation, ended net metering in 2015 and replaced it with grid-supply and self-supply rates to ensure grid stability. Since then, the state’s solar sector has been shrinking.

How to incentivize distributed generation without burdening non-generating customers and ensuring grid reliability – that is the ultimate question that Nevada and many other states will ultimately have to find an answer to.