By Ellis Talton

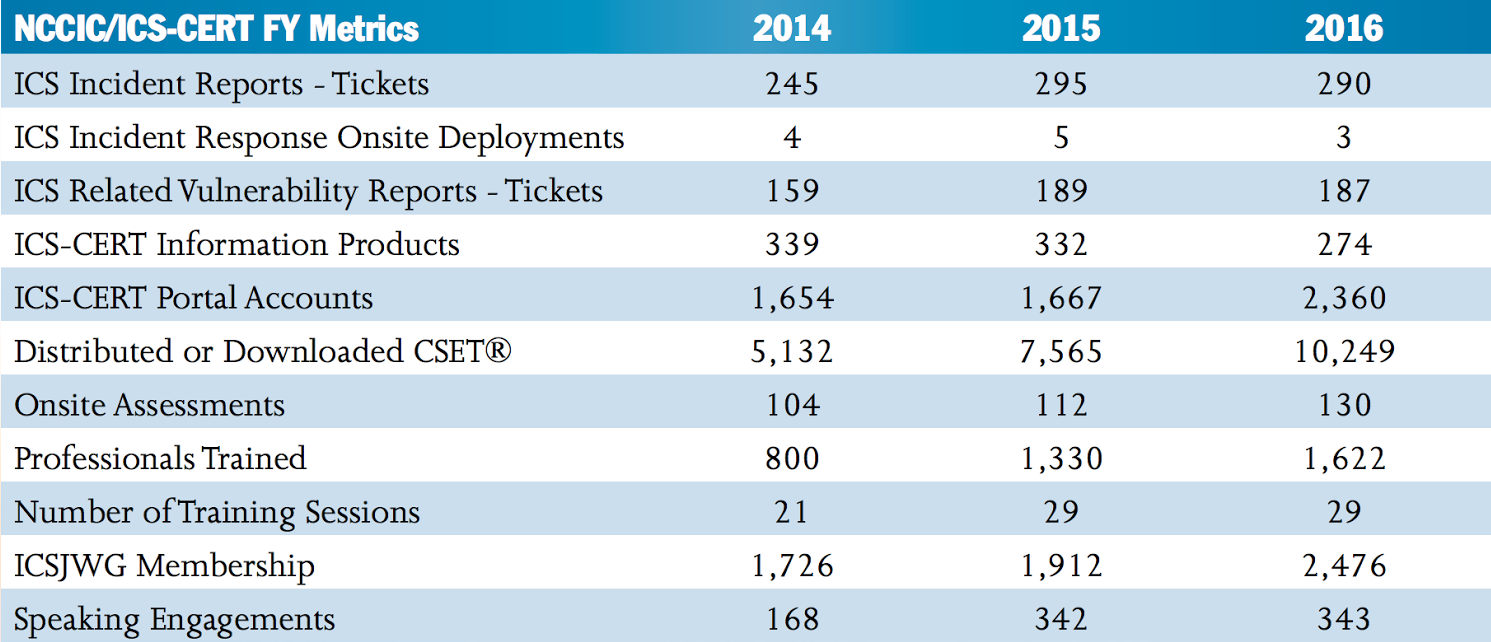

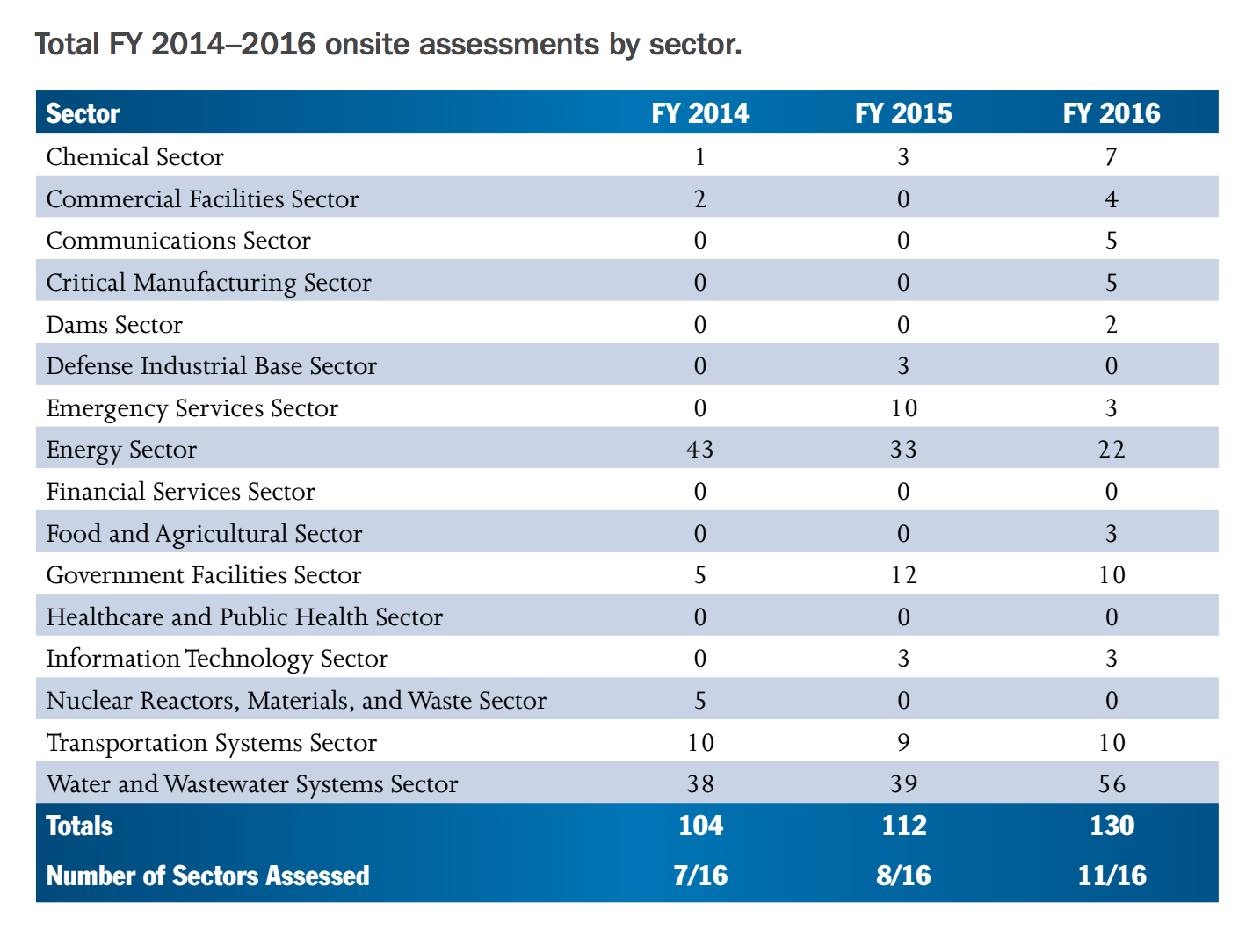

In March 2017, the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team, or ICS-CERT, (part of the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center which is part of Department of Homeland Security) published a report showing attempts to breach energy infrastructure in the US by foreign hackers increased by over 30 percent from last year. A total of 59 attempts were made to hack into energy facility IT infrastructure, representing 20 percent of all reported breach attempts. A total of 290 attempts were reported across 16 sectors for 2016.

Less than 60 attempts on the world’s largest internet-connected industrial control system (ICS) may not sound like a lot, but just one strike could be devastating at a large scale. What does an attack on an energy system look like? Take what happened in Ukraine in December 2015, an event considered to be the first-ever successful attack on a power plant system.

Hacker’s attempts to breach US infrastructure. Source: NCCIC/ICS-CERT

Black-out

On December 22nd, 2015, a hacking team known as Sandworm infiltrated Ukraine’s Prykarpattyaoblenergo control center (a public-private partnership in Ukraine that manages electricity transmission and supply) using phishing, the technique of luring users to open links and subsequently siphon valuable user and login data.

Hackers were able to breach the company’s security system and monitor the login data for employees, study the command and control system, and eventually change passwords and lock employees out of the system. The agents then moved unhindered throughout the operating system and controlled it at will.

According to a Wired article from March last year, employees could actually see cursors on computer monitors being manipulated from a remote location, helpless to stop the activity on the screen. Ultimately, hackers went through and manually disabled at least 30 substations (both 35 and 110 kV) across 3 power distribution centers and left a whopping 230,000 people without power for 3-6 hours. On top of this, they disabled backup supplies and jammed customer service phone lines. It was an unprecedented attack in its logistics and coordination and it highlighted major vulnerabilities that other systems around the world may experience.

The outage was relatively small compared to Ukraine’s population (only affected 0.005% of the population), and there have been other larger incidents cutting electricity around the world, such as Hurricane Katrina which left nearly 3 million people without power in 2005. Nonetheless, malicious attacks like the one in Ukraine can happen without notice– and can attack with no or very little notice. They can also be scaled to affect more serious infrastructure more permanently.

Thus the United States government reacted with a sweeping look at its own electricity infrastructure, and what may be done to protect it. It sent officials to Ukraine to study the aftermath, and back home a panel of Federal agencies– including the DOE, DHS, NSA, and FBI– briefed “asset owners and representatives” from all levels of government. The team briefed a total of 467 people and held these meetings in LA, Denver, Kansas City, Houston, Atlanta, Chicago, Washington D.C., and New York City.

The US is particularly vulnerable to disruptions: It has the most internet-connected systems in the world

Though we have not seen dramatic malware-caused power outages in the US like those in Ukraine, there have been scares in other sectors. The Department of Justice revealed in 2016 that it was charging 6 Iranian agents for an attack at a New York State dam in Rye Brook. Bowman Dam’s command and control system was breached by an Iranian team in August 2013, giving the foreign agents access to view information relevant to the operation of the dam, including water levels, temperatures, and the status of the sluice gate. Luckily at the time of hacking, the sluice gate was off-line for maintenance, otherwise, the system could have been manipulated and controlled remotely with possible devastating effects to electricity supply in the NY state.

Preparedness and response for critical energy infrastructure take place under the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Energy (plus dozens more sub-committees and agencies), which in 2015 published its most recent report on risk assessment for critical energy infrastructure. President Donald Trump appointed Former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani to lead the nation’s cybersecurity efforts in January 2017, although he has yet to issue any specific policy directives or Executive Orders on the subject.

Ultimately the US Government’s hand in providing security only goes so far, as 80 percent of the country’s energy infrastructure is privately-owned. Public-private engagement across senior executive leadership will be key, and events like NYEW will help to highlight areas of concern.

ICS-CERT provides government-funded security assessments for private companies.

____

Ellis Talton is a New York Energy Week 2017 Fellow. He worked as an energy journalist for The Oil & Gas Year in Istanbul, Turkey and covered the Middle East and Africa. He graduated from The University of the South: Sewanee with a Bachelor’s of Arts in French Studies and a focus on international relations.