By Janis Kreilis

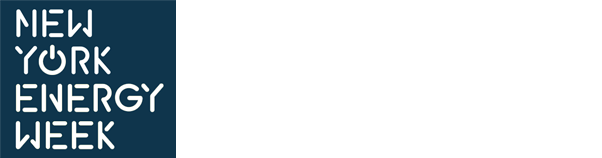

If anyone still did not believe it, you should now: the energy transition is officially happening. In 2015, natural gas, spurred by low prices thanks to a steady growth in production from the Marcellus, Eagle Ford, Bakken, and other shale regions, replaced coal as the largest source of power generation the U.S.

Source: EIA, BNEF

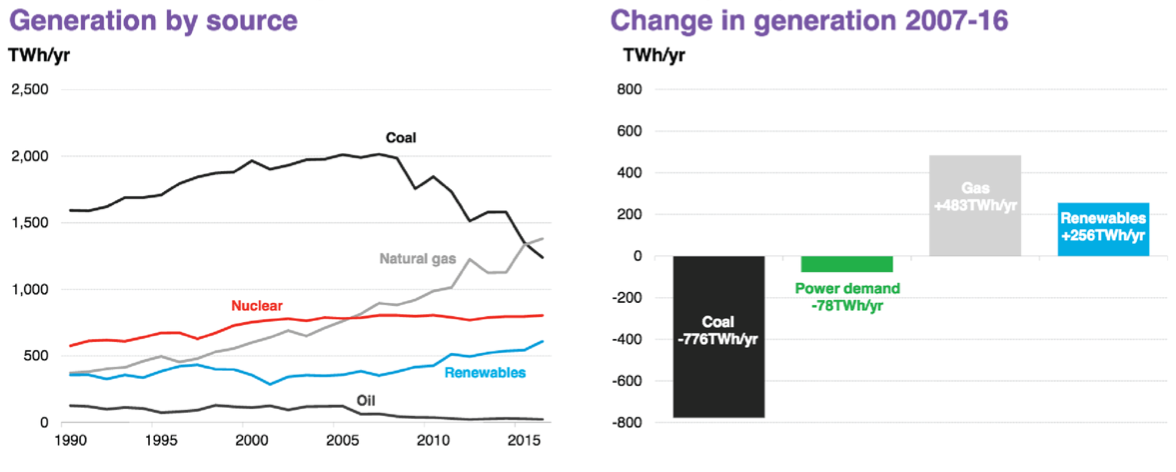

What’s more, renewables have shown incredible growth over the past decade. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, the total capacity of wind installations have increased by 262% between 2008-2016. If this already seems noteworthy, solar has gone up by a whopping 4,645% during that same period. Investments–a good indicator of where the energy system is headed in the future–betray a similar trend: globally, for every dollar invested in fossil fuels, there are two dollars invested in renewable energy.

Source: BNEF, UNEP

By now, it could be reasonable to assume that wind and especially solar technologies have entered a virtuous loop: supported by tax credits, they have reached the point where the economies of scale have pushed down the costs, which is further boosting deployment and pushing the costs even lower. The cycle goes on – Bloomberg has dubbed renewables “unstoppable”.

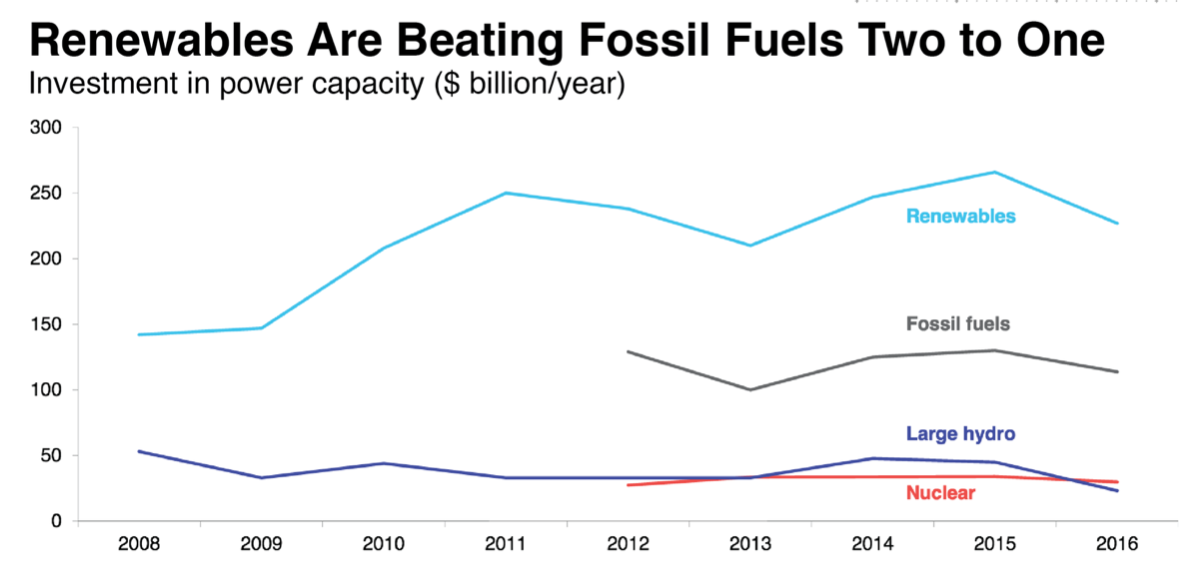

As good as this news is for the climate and, in the long term, for our wallets, it is important to take a look at the human side of this ongoing revolution. The fierce debates during the presidential election have sprouted an array of headlines on the job markets related to fossil fuels and renewables.

According to the Department of Energy, the U.S. employed 1.9 million people in electricity generation in 2016. Of those, 56% percent worked in the fossil fuel sector.

Source: New York Times.

The topic of coal versus solar jobs has received particular attention because of President Trump’s explicit support to the domestic coal industry, to which his critics have responded by pointing out that solar jobs outnumber coal jobs three to one. During the election campaign, some clean energy proponents suggested that the solar industry employed more people than the oil industry, which turns out to be false.

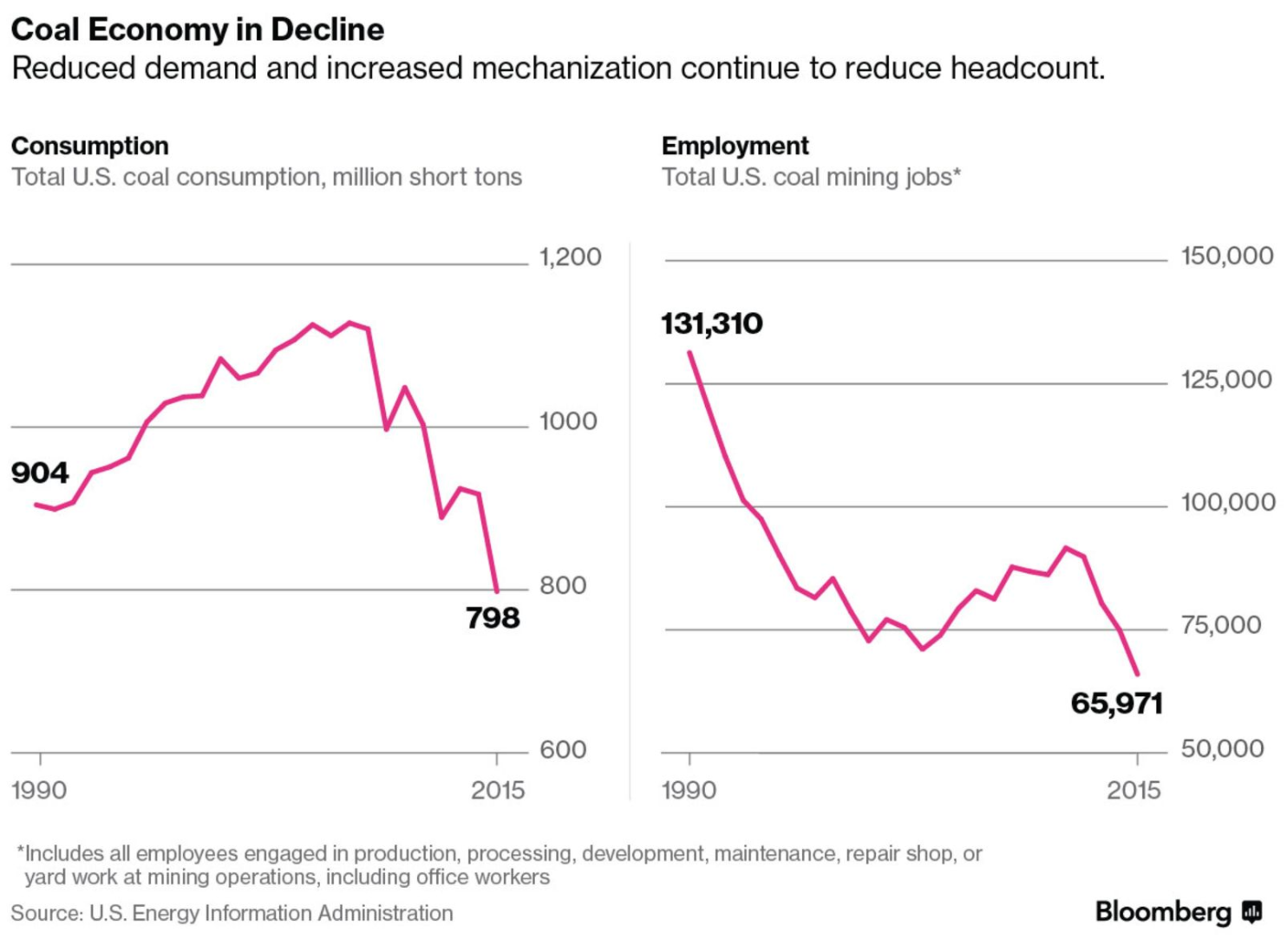

The coal industry has been particularly badly affected in recent years. As consumption has plummeted to the lowest level in 35 years, employment has followed suit. Currently, the industry employs the fewest people in several decades.

Source: EIA, Bloomberg

The first question is, can coal jobs be saved?

Unfortunately, two factors are playing against President Trump’s intentions to help revive the U.S. coal industry. Demand for coal has shrunk not because of renewables but because of the shale gas boom which has made natural gas–an adequate substitute for coal–cheaper, causing a wave of coal-to-gas conversions and gas-fired plant newbuilds. As long as the gas price stays low, coal will likely struggle against it.

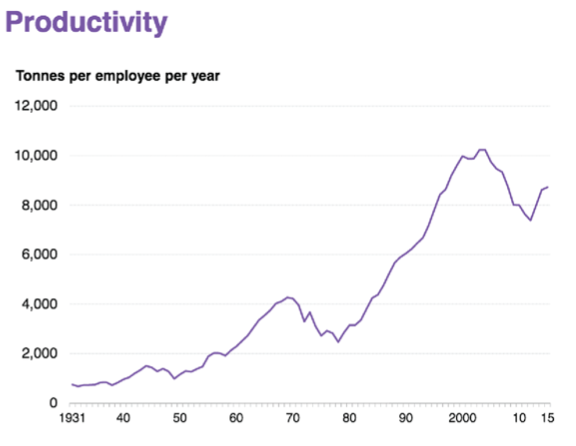

Furthermore, coal workers have been replaced by machines, as the mining equipment has grown in size and capacity. The industry has reported impressive productivity gains between 1980 and 2000, and this change is irreversible, too.

Source: BNEF, U.S. Department of Labor

What’s the story with solar jobs, then? After all, in 2016, the U.S. generated less than 2 percent of its electricity from solar while the industry employed almost as many people as the natural gas sector.

Several factors help explain this. First, solar is a new industry, and a lot of manpower is needed to set up the installations in this initial phase. Second, solar is much more labor intensive for the output it generates: solar creates fewer megawatt-hours per man-hour than any other sector. The argument goes that, as solar develops, and some of the installation jobs become automated by robots, this difference will fade away.

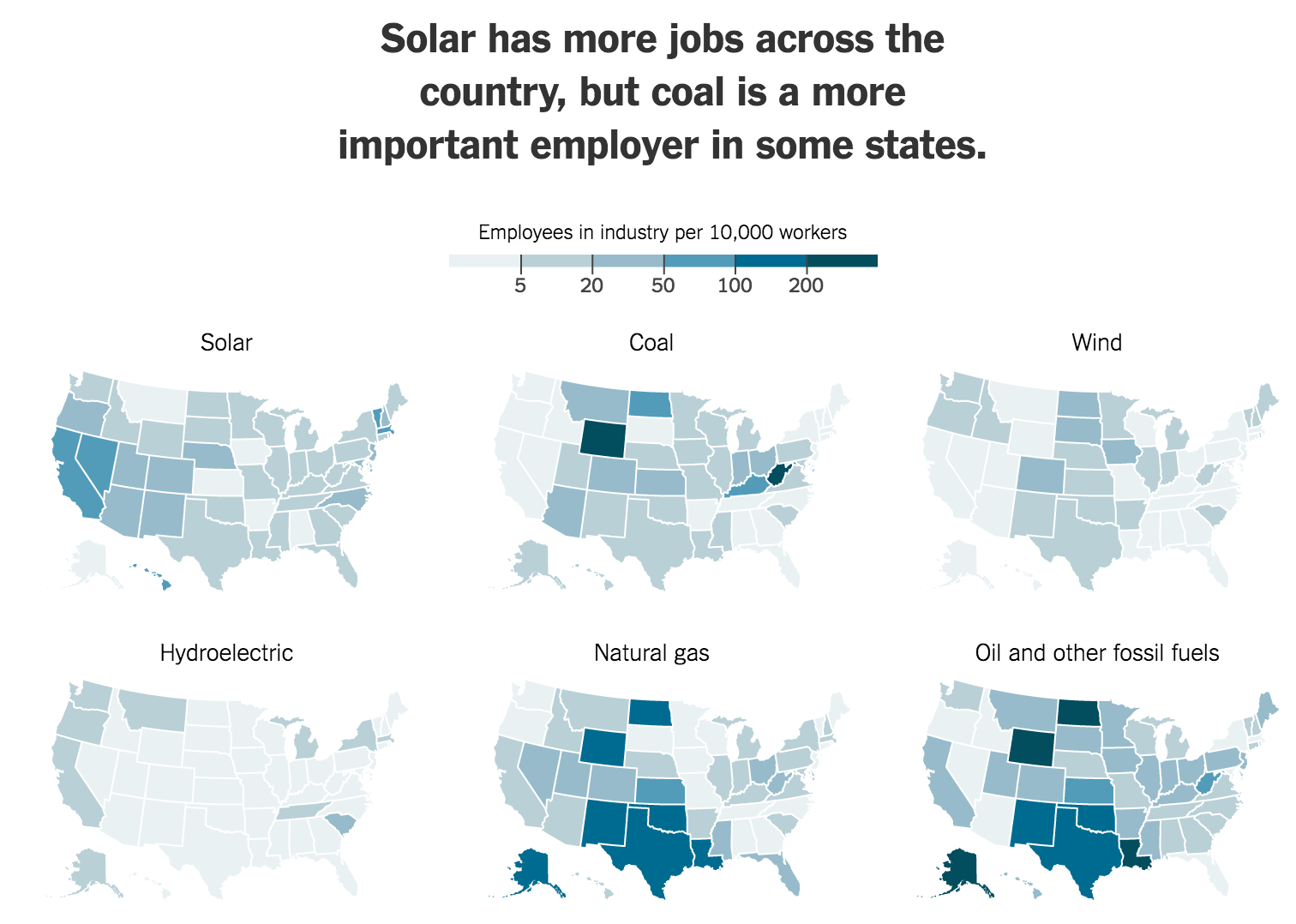

A crucial factor that helps explain the “us” versus “them” framing in this debate on energy transition is that both solar and coal industries are relatively well concentrated and these geographical locations do not coincide. Solar is strong in the southwest, Hawaii, and some states in the east, while coal is a major industry of Wyoming (3 percent of total employment) and West Virginia (2 percent). Even if it was possible to transform the redundant coal miners in those two states into solar professionals, there would simply not be enough jobs for them.

Source: The New York Times

Instead, some entrepreneurs have started to experiment with programs that train coal miners to become programmers. According to Rusty Justice, who has founded Bit Source, a coding company that trains and employs ex-coal miners in Kentucky, “Coal miners are really technology workers who get dirty.”

As the energy revolution continues, both government support and commercial initiatives will be needed to help the tens of thousands of people who will find themselves out of job over the next few years. The sooner we start, the better.