Can Nuclear Power Bounce Back?

By Hudson Kuras

American nuclear power has been in a tenuous position for the past few decades. The Three-Mile Island accident in 1979 and changing economics put nuclear development on the back burner of America’s energy infrastructure plans. Dozens of planned projects were cancelled over the next two decades and it took 33 years for the NRC to approve construction of a new reactor. Despite this lapse in development, EIA data shows that nuclear power was still responsible for 20% of the electricity generated in the US in 2015. In recent years, the outlook for nuclear power in the US has fluctuated between growth and decline. Regulatory changes, fuel prices and nuclear accidents worldwide play a role.

In 2005, the Energy Policy Act provided new nuclear plants with cost overrun support from the federal government. Momentum grew in 2010 when President Obama, citing concerns about carbon emissions, announced loan guarantees for two reactors and a plan for additional loan guarantees in the future. Federal intervention to combat climate change gave nuclear power a positive outlook. That changed after breakthroughs in shale gas production and the Japanese Fukushima Accident in March 2011. The accident drastically reduced public and political support of nuclear power. The abundant supply of cheap natural gas, made possible by advances in hydraulic fracturing, created a competitive source of base load electricity. These political and economic developments reversed the outlook of American nuclear power.

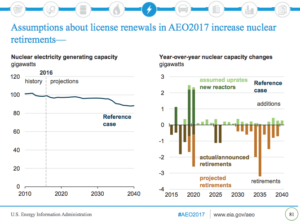

So where is US nuclear power in 2017? This past October, a second reactor at the Watts Bar Nuclear Generating Station began commercial operation making it the first new addition to America’s nuclear fleet in 20 years. There are currently four reactors under construction in the US: two at Summer Nuclear Generating Station in South Carolina and two at the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant in Georgia. These reactors are expected to begin operation between 2019 and 2021 adding a combined capacity of 4.5 GW to our nuclear fleet. According to the EIA, capacity additions will also come from uprates at existing reactors, adding a projected 4.7 GW by 2040. Despite these additions, the EIA projects the retirement of 9.4 GW of nuclear capacity by 2020 and another 10.6 GW of retired capacity through 2040 as older plants reach maturity. That’s a net reduction of more than 11% of today’s nuclear capacity.

EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2017: Projected Changes in Nuclear Capacity

There are multiple reasons for the decline of US nuclear capacity. Despite efforts to increase nuclear development under both the Bush and Obama presidencies the trend of deregulating electricity markets and low-cost fossil fuels hinders this development. In a regulated electricity market, the cost of capital investment is passed to the consumer in a temporary rate increase. In a deregulated market, the retail customer can buy their electricity from the cheapest producer; a rate increase can’t fund the high capital costs of nuclear plants because consumers can buy their electricity elsewhere. Even in regulated markets, nuclear needs specific conditions to be profitable. Currently, nuclear’s profitability is squeezed on one side by low-cost natural gas plants that, under current prices, provide base load power at a lower cost. It is squeezed on the other side by subsidies that make renewable energy competitive.

There is a narrow path to growth. Recently, unprofitable nuclear plants in the deregulated markets of New York and Illinois have avoided shutdown after state government provided them with zero-emission subsidies normally reserved for wind and solar facilities. If other states follow suit, it will extend the lifespan of reactors throughout the US. To see America’s nuclear fleet grow, it will take a significant increase in the operational costs of gas-fired power plants. Increasing natural gas production makes that unlikely unless there is a tax on carbon emissions. Alternatively, lower natural gas prices, a breakthrough in battery storage or a serious accident are all poison pills that can kill nuclear’s future in the US.

___

Want to add something about nuclear power? Are there future topics you’d like to see a post about? Contact me: hk@nyenergyweek.com

Hudson Kuras is the New York Energy Week 2017 Fellow. He graduated from Columbia University in February 2017 with a Bachelor’s of Arts in Sustainable Development concentrating on energy and resources. He has worked as a Summer Analyst at Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. and as a non-profit Consultant with Columbia’s Earth Institute.

Hudson Kuras is the New York Energy Week 2017 Fellow. He graduated from Columbia University in February 2017 with a Bachelor’s of Arts in Sustainable Development concentrating on energy and resources. He has worked as a Summer Analyst at Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. and as a non-profit Consultant with Columbia’s Earth Institute.