Renewable energy in excess threatens the reliability and costs of electricity

By Janis Kreilis

Although the Trump Administration has publicly expressed its support for the U.S. domestic fossil fuel industries, namely coal, oil, and natural gas, market dynamics coupled with favorable policies continue to push renewables.

On March 23, California hit a new record: just before noon, the California ISO (CAISO) served 56.7 percent of all demand with renewable energy. Solar and wind power, combined, hit another peak at 49.2 percent on that same day.

Great, then with Clean Power Plan or no Clean Power Plan, California already appears well prepared to meet its target of 50 percent renewables by 2030, signed into law in 2015. (A new proposal, currently under debate in the state assembly, sets 50% by 2025 and 100% by 2045.)

But can renewables be too much of a good thing?

Turns out, yes. In February, CAISO warned that favorable hydro conditions and growing solar capacity could lead to curtailments of renewable capacity anywhere between 6 GW and 8 GW in 2018, potentially rising to 12 GW by 2024.

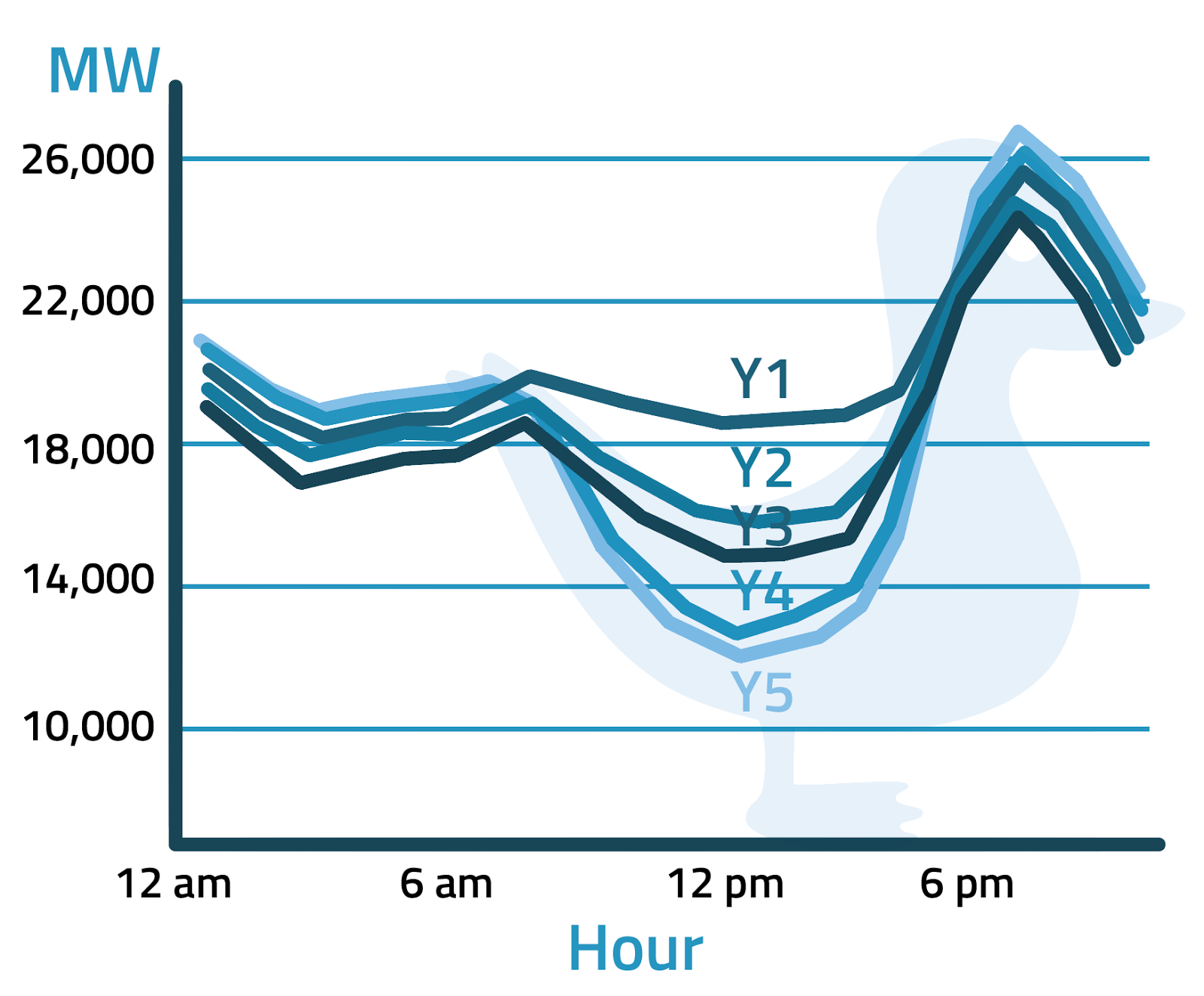

The issue here comes from the daily load curve. At any given moment, the grid operator needs to balance the generation of electricity with the demand for it. However, as more customers install solar panels, the daily load curve drops in the middle of the day during peak generation. At sunset, however, electricity demand peaks as consumers return home from work, and the utility has to turn on inefficient, open-cycle gas plants (typically called “peaker” plants) to satisfy that demand since the solar plants do not generate electricity in the evening.

Sample duck curve. Source: EnerKnol

According to Scott Madden, a consultancy, this issue – known as the “duck curve” – has worsened in recent years. Since renewable energy is dispatched first in California, having too much of it may force to shut down some of the baseload plants which are expensive to restart again at night when renewable generation falls. This leads to reliability issues and increases costs, hence the curtailments.

One way to address this issue would be through energy storage; by storing excess energy in the middle of the day and releasing it in the evening, the peak could be flattened out. In March, the California Public Utilities Commission (CA PUC) proposed to double funding for the state’s Self-Generation Incentive Program, with 85 percent of the funds allocated to energy storage projects.

In 2016, the CA PUC also directed investor-owned utilities in Southern California to fast-track additional energy storage projects to increase reliability. In February 2017, the largest lithium-ion battery storage facility opened in San Diego. With a 30-MW, 120-MWh capacity, the plant can serve 20,000 customers for four hours, according to its developers SDG&E and AES Energy Storage.

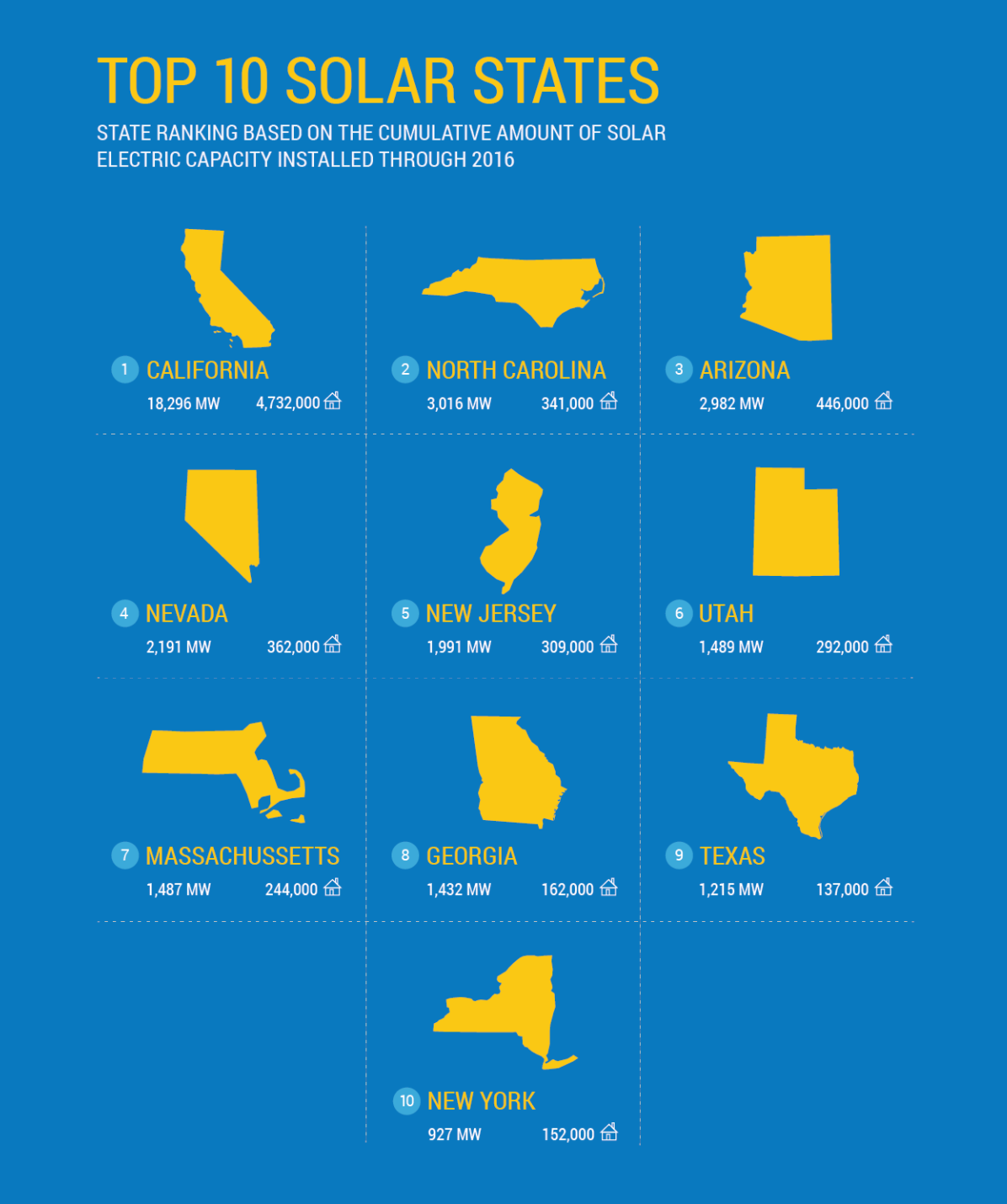

Through projects and policies like these, California is pressing ahead in a realm that is still quite technologically new in the industry. The lessons, however, will apply nationwide. According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, California led the nation in 2016 with more than 18 GW of installed solar capacity. As others, including Hawaii, Arizona, Nevada, and New York, follow suit, developments in California will show how to use the full capacity of renewables while maintaining grid reliability and reasonable costs of operation.

Top 10 solar states. Source: SEIA